Graham tells the story of how desktop exercises were used to test integration and contingency plans for Games transport

In the previous post, I explained the Olympic Delivery Authority’s (ODA’s) assurance and readiness-testing work, and described how the opening of Westfield at Stratford, just under a year before the Games, was used as a test of the transport system.

The other part of the readiness programme I worked on was the set of three transport desktop exercises. These brought together the transport operators and other key players, over several days each time, to test the readiness of their plans for Games-time operation.

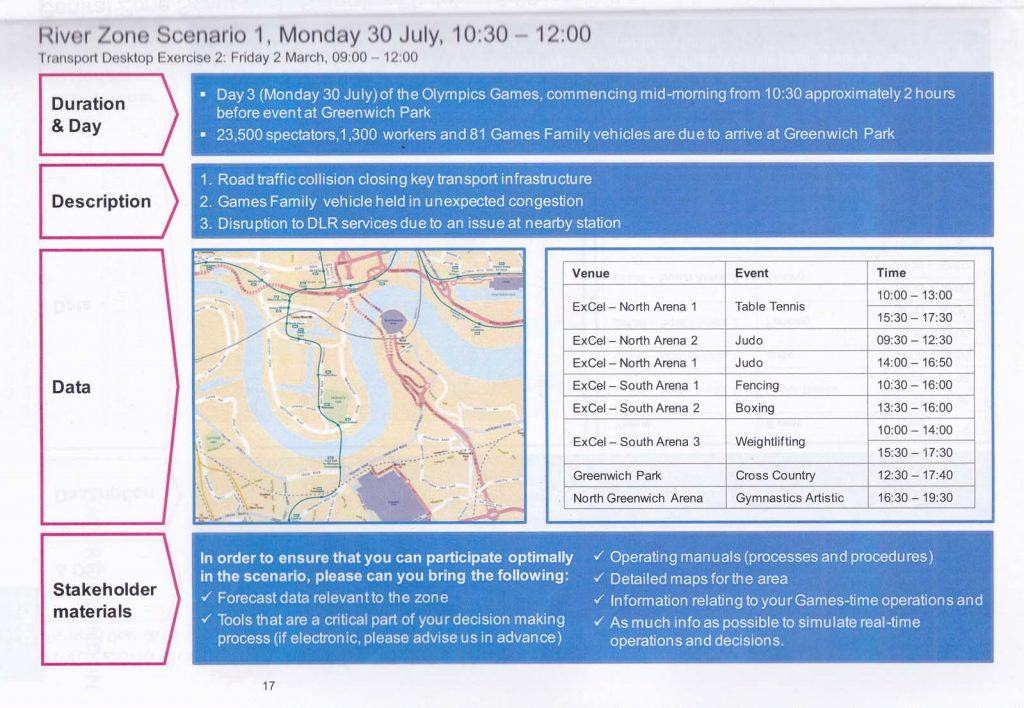

The first exercise looked at particular venues or areas, and focused on making sure that individual organisations’ plans meshed with each other. The subsequent exercises looked at contingency plans: whether they were in place and well-practiced, and whether these too meshed with each other. Transition to arrangements for the Paralympics, and a focus on accessibility issues, also featured.

Participants included not only the transport operators but also the emergency services, the Transport Coordination Centre (TCC), the Olympic Park Transport Integration Centre (OPTIC) and LOCOG, the body dealing with the administration of the Games themselves. LOCOG would be in charge of getting the Games family around from hotels to training and competition venues.

Ops room

The exercises initially took over the ballroom of a hotel, and later Methodist Central Hall. The centrepiece of each session was a large table covered with a map of central London or the other venue areas. Major venues and landmarks such as Buckingham Palace, the North Greenwich Arena (alias the O2) and the ExCeL centre were picked out with tiny models. Roundels and double-arrows on sticks denoted critical stations. It had a touch of the classic war-movie ‘operations room’. We even had those little sticks for pushing the things across the table. It was fun to organise, an excellent ice-breaker on the day, and the tabletop map was valuable for pointing to places. But the game pieces and brooms weren’t really needed in the end.

To look at contingency plans, scenarios were set up involving a particular day of the Olympics or Paralympics, and imagining that there was a particular item of disruption somewhere important on the network: perhaps a line closure, or a road accident. Participants were then asked to talk about what action they would take in response. This might lead to impacts on other participants, which might need to be explored. And so on. Useful things emerged in discussion. And if it was going too easily on the contingency planning front, the facilitator might inject extra disruption to spice it up. It was deliberately planned to be a discussion-based format, not a tedious ‘going-round-the-table’.

RAG status

Each participant also had a set of red, amber and green cards for an occasional show of hands: Green meant that a tried-and-tested contingency plan for a particular problem was in place. Amber meant a plan in place but not tested, and red meant some work still to do.

It quickly became apparent that not only were many of the basics already in place, but that the transport system was already familiar with dealing with this kind of challenge (although not necessarily on an Olympic scale). A typical scenario would begin like this:

Facilitator: It’s 0800 on day X, with events in Hyde Park, The Mall and Horse Guards Parade. There’s a problem at Westminster station, which has had to close. Crowds are now building up outside. Underground, how do you respond?

Underground (laconically): That’s every morning at Victoria for us.

But there were plenty of new challenges to be tackled, including arrangements within the ‘last mile’ around the venues, ensuring that Games family vehicles could respond to disruption while en-route, and issues thrown up by the sheer scale of the combined spectator numbers. The networking opportunities also seemed to be appreciated.

Note-takers jotted down any points of risk that were identified – essentially, issues where the arrangements were not already confidently established – and the ODA got a good feel for how things were going. And over the course of the exercises I certainly saw how the plans progressed and became more coordinated.

Top advice

Each day began with a pep-talk from a VIP guest. The best, in my view, was from a seasoned transport operator who eschewed the usual inspirationals and went for the practicalities. “Look after your people,” he advised. They would give their all for the Olympics, then have to do it again for the Paralympics. Operators should watch for burnout, and make sure people got a good break between the two sets of Games. I thought this advice alone was worth turning up for. It came from a Mr P. Hendy – whatever happened to him?

Next in this series: Did all the planning pay off? Part 6 looks at how London’s transport network actually performed during the Games.