It’s a Brucie Bonus for the economic case – but you’ve got to play your cards right. Graham explains how the updated guidance fits in.

In my main post on the TAG updates for May 2025, I mentioned the updated guidance on dependent development (DD), and promised a deeper dive into it.

At the time of writing, we don’t have the updated unit itself. But the Forthcoming Change notice gives a lot of detail and includes extracts from the new version. (Update: the unit has now been published.)

What’s it all about?

DD is about situations where a transport scheme unlocks development that couldn’t happen without it – for example, a large housing site that needs the extra transport capacity that a new road or public transport scheme would provide.

TAG allows you to claim the land value of such development as a scheme benefit, although you have to net-off the incremental congestion disbenefits caused by the development traffic and make some other adjustments. The DD benefits can often boost an otherwise limited economic case.

It’s part of the larger category of wider economic impacts (WEIs), also known as wider economic benefits. We think of WEIs in three levels:

- Level 1: no WEIs (or at least, none significant enough to be worth assessing).

- Level 2: Connectivity impacts (also known as ‘static’ impacts). These are impacts from people and businesses being better-connected through changes in the transport network. These are the relatively simple and routine WEIs and there are TAG methods for assessing them. The benefits count towards the ‘adjusted BCR’.

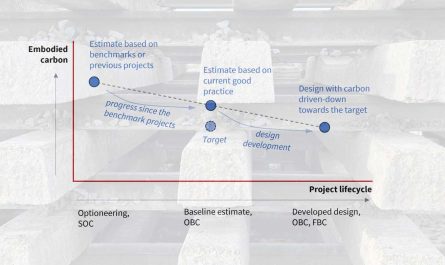

- Level 3: Dynamic impacts (also known as ‘structural’ impacts). These are where you expect and quantify land-use change as a result of your investment: so people or jobs not just being better connected, but moving in response. Generally these impacts go beyond TAG methods, into the world of supplementary economic modelling – on which my previous post covered the latest guidance. And these benefits can only count towards the ‘indicative BCR’.

DD is level 3, as you are quantifying land-use change. But it’s a special case as there is a TAG method for it, and it’s more routine than the other level 3 analyses. I see it as a sort of level 2.5 in analytical terms. But it’s still level 3 for BCR purposes.

The DD calculations

The guidance provides a step-by-step set of scenarios to run (known as P, Q, R and S) and equations to follow. The method does involve a lot of assumptions and judgments, such as about what parts of the development are actually ‘dependent’, economic factors such as whether the houses or jobs would happen on another site instead (if so, it’s not actually dependent), and what level of congestion would be seen as blocking development. Use of ranges and sensitivity tests is therefore always sensible.

There was also a serious BBC documentary about this.

Nevertheless, the DD benefit figures are unsurprisingly seen as not particularly robust, and can’t count towards the initial or even the adjusted benefit-cost ratio (BCR). But they can count towards the indicative BCR and the final VfM category – I posted about this last year when the indicative BCR was introduced in DfT’s updated Value for Money framework. It’s not just a Brucie bonus: the DD might save the day by lifting the scheme into a more acceptable VfM category.

The updated guidance

DfT says the updates are to address two issues: defining DD more clearly, and a tendency for appraisals to overestimate the scale of DD benefits. To fix them, three elements are involved.

Firstly, there will be expanded guidance on defining dependent development. The FC notice helpfully includes detailed extracts. The new material covers:

- Explicitly giving two possibilities for DD: either where land would not have been developed at all without the transport scheme (eg if it is inaccessible) (“directly enabled”), or where a development could be part-built without the scheme but the remainder needs the scheme to alleviate a transport capacity constraint (“partially enabled”). The second of those is already covered in the guidance; the first is not explicitly stated but in practice has always been seen as a possibility.

- Explicitly saying that land-use change as an unintended consequence of a scheme can’t count as DD. Nor can situations where a transport scheme makes an area generally “more attractive” to live or work in be used to generate DD benefits.

- DD needs to be genuinely additional – in other words, it wouldn’t have just happened on another site in the absence of the scheme. Again this is already covered in the guidance, but towards the end of the process as part of the valuation stage. The new guidance brings this more to the fore – in effect, asking you to consider, from the start, whether the development is additional (hence DD) or just displaced from another site (not DD).

To reinforce these points, there are helpful new tables to help you decide what does and doesn’t count. One of them introduces the phrase ‘Dependent Additional Development’ or ‘DAD’, which I rather like as a way of making the point that DD has to be additional not displaced. I might start using that.

The update also makes the point that the same issues apply to development as part of a larger-scale regeneration or non-transport-led intervention: you still have to identify a dependency that is solved by the transport element.

| Name | Description (including housing development example) | Is it dependent? | Is it additional? Does it add to UK housing stock relative to BAUD? | Is it part of the DM or DS, or both DM and DS? | Are the residents assumed to live elsewhere in DM? |

| Business as usual development (BAUD) | The development that failed the dependency test but is commercially viable in DM. e.g. house building that happens anyway. | No | n/a | Both DM and DS | n/a |

| Attracted development (AD) | Not dependent, but only viable or happens in DS. e.g. transport intervention means housing development is viable and goes ahead. | No | Yes | DS | Yes |

| Dependent displaced development (DDD) | Dependent development but it’s displaced from elsewhere. e.g. transport intervention unlocks land enabling housing development to go ahead. Without the transport intervention the houses would have been built in a different location. | Yes | No | Both DM and DS | Yes |

| Dependent additional development (DAD) | Dependent development and is additional e.g. transport intervention unlocks land which means housing development can go ahead. Without the transport intervention the houses would not have been built. | Yes | Yes | DS | Yes |

I get the impression that this element is simply reinforcing existing guidance and good practice, rather than being substantive change. Certainly all the DD assessments I’ve worked on were done properly, and their thinking process was is in line with the new guidance, such as making a fair attempt to estimate what was genuinely DAD. I wonder, reading between the lines, whether the update is in response to some schemes having taken too sweeping a view.

The second element is additional guidance on how to deal with uncertainty around DD benefits. This includes the need to think about this uncertainty in the economic narrative (the logical rationale behind the economic case), not just in the number-crunching itself:

- Is DD a key part of the scheme’s expected benefits? If so, the uncertainties become important.

- What proportion of the development is DD? This affects the uncertainty, and is a nuance that I hadn’t previously picked up. Counter-intuitively, the lower the DD percentage, the higher the uncertainty. The FC notice puts it like this. If (say) 20% of a development is DD, then you don’t start accruing DD benefits until after 80% buildout. But if it’s 80% DD, then once buildout goes beyond the first 20% you start accruing the DD benefits, and at the same 80% buildout you’ve accrued most of them. I’d add that the same could apply to inaccuracies in the estimates: if your estimate is for 80% DD, then you know you will get a lot of DD benefits even if the reality turns out to be only (say) 60%.

- Might local planning constraints, such as regulatory or land scarcity constraints, limit or slow down the delivery of DD? This seems to be bound up with the over-estimation issue; the FC notice is not clear but I would interpret it as meaning “how sure are you that the DD will actually be delivered?”

The third element is a new sensitivity test (actually a switching-value analysis) that will need to be applied to the DD results. This is really about the potential for under-delivery of the DD, and understanding the risk this presents to VfM.

The test asks two questions: how much under-delivery of DD would drop your scheme down to a lower VfM category, and how does that compare to the evidence on actual under-delivery?

The underlying issue is a concern that schemes tend not to deliver as much DD as the appraisals assume, at least on the promised timescales. The FC notice describes research by the What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth, looking at six road schemes and the associated dependent housing development in their appraisals and in reality. The research found that five of the six were unlikely to deliver the assumed amount of DD by the assumed dates (or within 20 years of completion if no date was given). DfT takes this as suggesting “a strong tendency to overestimate the scale” of DD, although acknowledging that the research only looked at road schemes and delivery of housing.

To cut a long story short, the guidance comes up with a “contextualising range” of around 30-50% under-delivery to capture this tendency. Using this, the switching-value process is:

- Take your indicative BCR (which includes a central value of the DD benefits)

- Keep all the other benefits unchanged

- See what percentage reduction in DD benefits would be needed before you drop down into a lower VfM category

- Compare that against the ‘contextualising range’ of 30-50% under-delivery, and hence see the level of risk that you will indeed drop down a category.

I’m not sure I would place too much emphasis on the exact figures produced by the research – it’s a limited number of projects and, as was stated, focuses on roads and housing. But the basic principle is sound: that DD benefits are an area of considerable uncertainties, and I suspect that there is indeed genuinely a tendency to be over-optimistic (as distinct from merely a range of uncertainty) on timescales for buildout.

With that caveat, the test itself is a reasonable and very easy one to do. You should be doing this kind of sensitivity testing anyway. I’d just mention a couple of nuances:

- It assumes that the DD has bumped you up a category – which is often the case, and this is exactly when understanding the uncertainties is most useful. If it hasn’t, clearly the test doesn’t really apply (it will just confirm the obvious).

- In appraisal terms, the basic issue is the same whether the undershoot involves not delivering at all, or just delivering slower than expected.

- Strictly speaking, under the November 2024 DfT VfM framework the indicative BCR doesn’t have an associated VfM category in its own right; you skip from the provisional VfM category (reflecting the adjusted BCR) to the final one which reflects not just the indicative BCR but all the other factors that go into it. In practice, however, a VfM category can be implied from the indicative BCR and people will just quote it, which is not unreasonable.

And that’s the latest TAG guidance on dependent development.

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Updated 2 June 2025 to note that the updated unit has now been published.