Graham rounds-up the latest TAG updates. What’s changing, and what does it mean in practice?

Last month (December 2025), the UK Department for Transport (DfT) published the latest updates to its Transport Analysis Guidance (TAG).

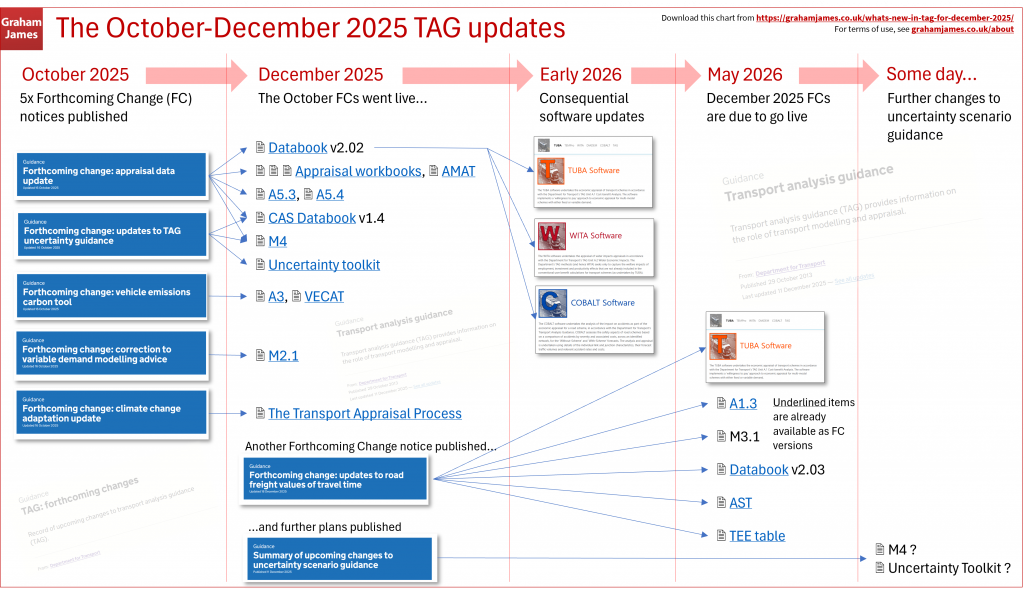

These were originally set out in five forthcoming change notices in October 2025. Although these cover a lot of different corners of TAG, most are relatively straightforward, with only a couple of substantive changes to specific requirements or processes. But one of them is also a harbinger of further changes to come.

I’ve updated Tag-at-a-Glance to give a unit-by-unit (or workbook-by-workbook) summary of what’s new. Although released in December, the new material is generally dated November 2025 in line with the usual schedule for such releases.

The main areas of change are:

- Updated economic and demographic data

- Updates to some of the Common Analytical Scenarios (CAS)

- Important changes to the underlying guidance on dealing with uncertainty

- The new Vehicle Emissions Carbon Tool (VECAT)

- New guidance on climate change adaptation

- And a range of minor updates, clarifications and corrections covering values of travel time, variable demand modelling (VDM), rail performance impacts and marginal external costs (MECs)

Alongside these, DfT have published a look ahead to further changes to uncertainty guidance (which I’ll also briefly mention) and a forthcoming change on road freight values of time, due to go live in May 2026 (which I’ll cover separately in due course).

Updated economic and demographic data

The new version of the TAG Databook (v 2.02) includes fairly routine updates to the annual parameters. This time around, the updates reflect:

- The latest outturn (ie what has actually happened) data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) on household numbers and construction prices

- The Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR’s) latest medium- and long-term economic forecasts

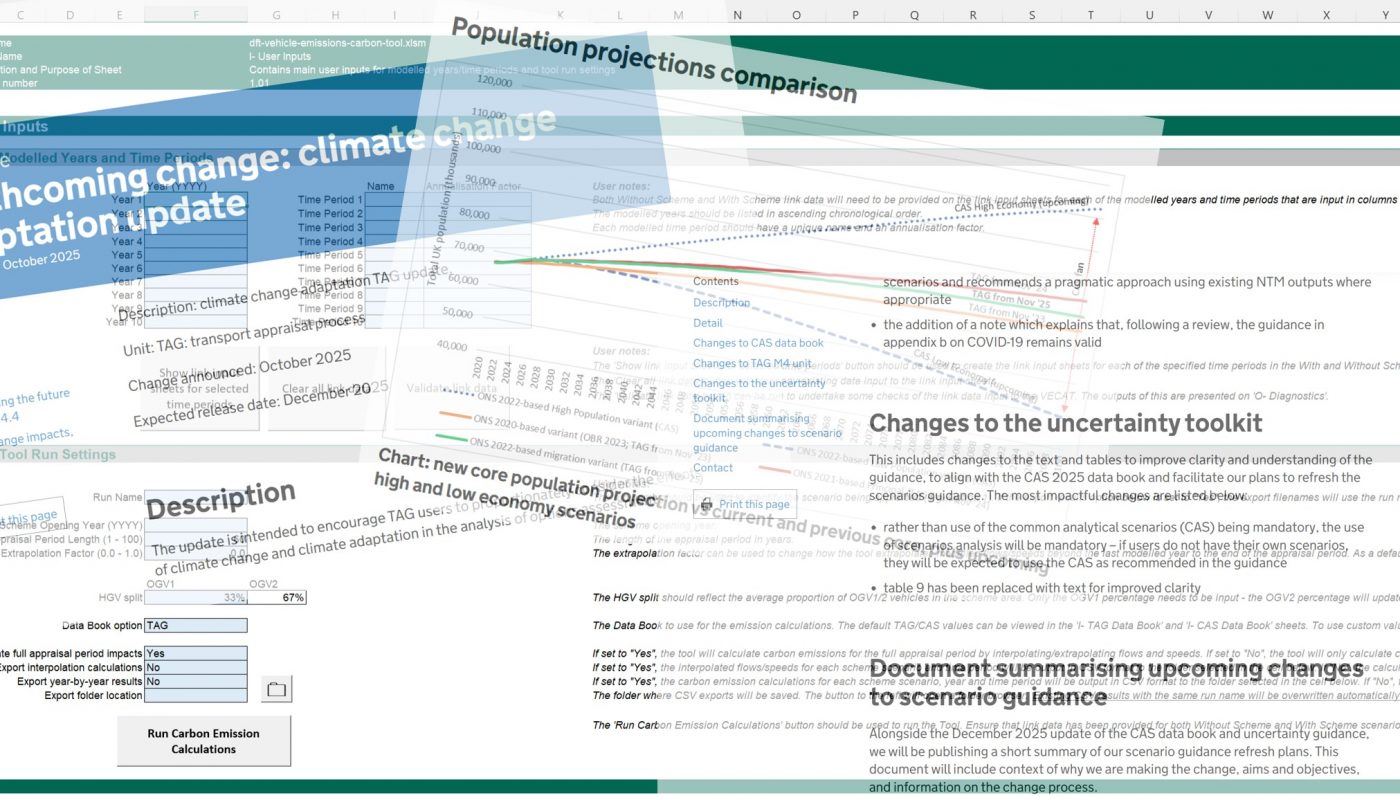

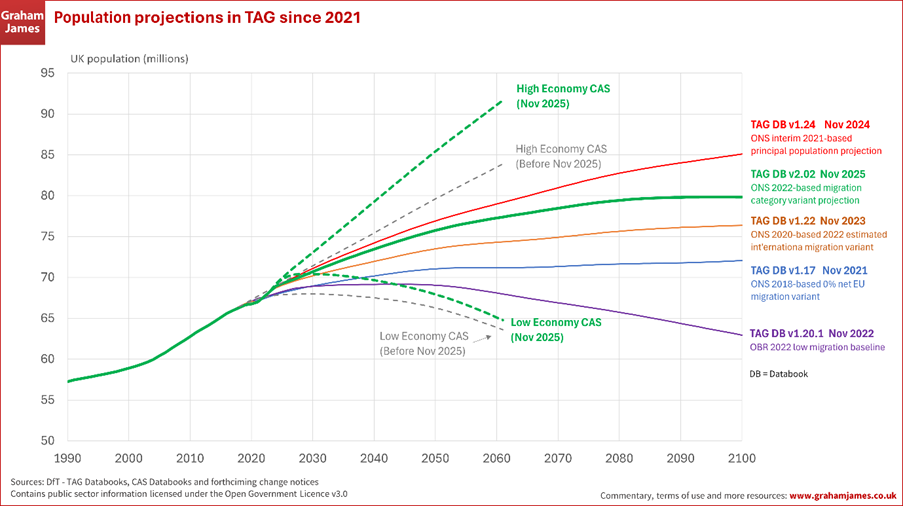

- A change in the population projection used by OBR. DfT has, as usual, flowed this change into TAG for consistency with the other OBR-generated data. The new population figures are slightly lower than before, but are still within the range of different projections that have appeared in the Databook in recent years (see chart below). I’ll say more about this in a follow-up post.

As always, the appraisal workbooks that use these parameters have been updated to match, as has the Active Mode Appraisal Toolkit (AMAT).

Updated Common Analytical Scenarios

There’s also a new version of the Common Analytical Scenario (CAS) databook, with updates to the annual parameters for some of the scenarios:

- The High Economy and Low Economy scenarios have been updated with the latest economic and demographic data, to bring them back into consistency with the latest TAG core scenario. The basic principles of how they differ from the core are unchanged: higher/lower population (and consequently higher/lower households and employment), and higher/lower GDP per capita, than the core. I’ve included their updated population projections on the chart above.

- The Technology, Vehicle-Led Decarbonisation and Mode-Balanced Decarbonisation scenarios have also been updated, to reflect new fleet mix modelling. This affects the mileage splits, fuel efficiencies and fuel costs.

The Regional scenario and Behavioural Change scenario are unchanged. But there’s a new cautionary note about the latter, which DfT considers may not be a suitably-stretching lower bound for future travel demand.

Uncertainty: what’s to come is still unsure

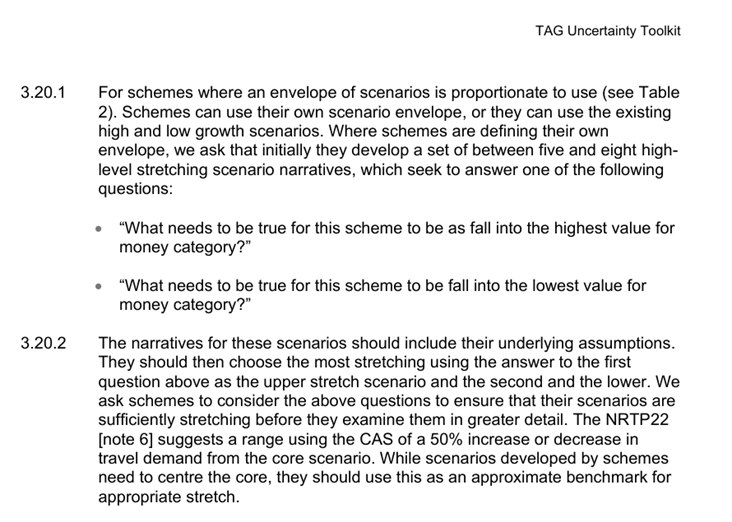

As well as updates to these scenarios, there has been a more fundamental change to the guidance around scenario-analysis (aka ‘uncertainty analysis’) in Unit M4 and the Uncertainty Toolkit. Previously, DfT expected projects to use the CAS, or at least some of them, for this. Now this kind of analysis is still mandatory, but need not involve the CAS. Scheme promoters should develop their own scenarios, and should only use the CAS if they can’t do that.

The basic approach to deciding how much analysis to do (set out in Tables 1 and 2 of the Uncertainty Toolkit) is essentially unchanged. The only tweak here is that the scale and nature of benefits (including whether they go beyond purely transport benefits) is an extra factor to consider in deciding whether a scheme goes into the low, medium or high impact level.

The critical change is that references to the CAS are now simply references to ‘scenario analysis’. Thus, for example, the previous minimum requirement to consider the CAS qualitatively has become a requirement to “conduct scenario analysis, which at a minimum is qualitative and covers national level uncertainties, local level uncertainties, and any other scenarios [you] deem relevant” (source).

So DfT seems to be giving up on trying to make people use the CAS. But they are not giving up on the principle of running scenarios. Nor, on my reading, is there a reduction in the expected number of scenarios that need running or considering. Anyone who had been hoping for a more light-touch approach might not be in luck.

The detailed guidance on how wide or ‘stretching’ a basket of scenarios to use has also changed. It takes some untangling, after which you might need to lie down in a darkened room.

There is also new explicit guidance on reflecting local-level uncertainties, including advice to focus on the uncertainty in the ultimate social, environmental and economic impacts of schemes, not just the level of immediate transport benefits. The guidance doesn’t give any specifics, but this seems a good hook on which to hang the ‘policy-on’ type of scenarios that some local authorities use alongside the TAG core. It could also apply to a ‘local plan growth scenario’ as sometimes used by authorities who consider the NTEM-based Tempro road traffic growth factors in the TAG core scenario to be unrealistic (there is existing supplementary guidance about this). Of course, in DfT terms this is still just about uncertainty – it doesn’t take away the primacy of the core scenario.

But this round of changes is just a first step in what is potentially a major change of tack from DfT on the CAS and the whole issue of scenarios for dealing with uncertainty. I’ll try to cover this – and the pros and cons of the CAS – in more detail in a future post. For now, you can read about DfT’s plans here in their own words, or here (£) on TransportXtra. And enjoy the CAS while they last.

Strictly speaking, that’s Kaz not CAS. But we’ll enjoy this anyway.

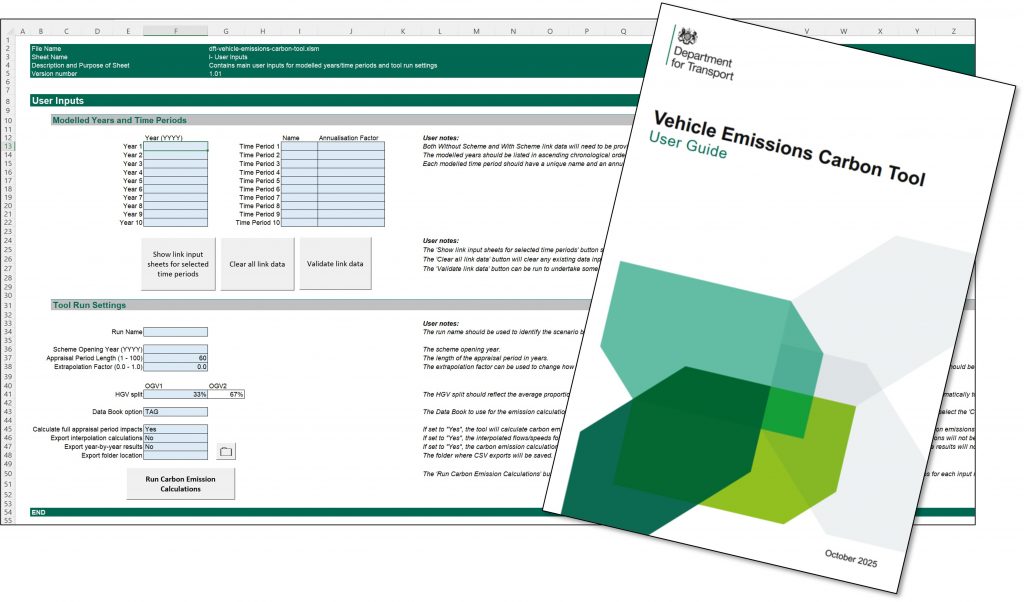

The new Vehicle Emissions Carbon Tool (VECAT)

The Vehicle Emissions Carbon Tool (VECAT) is a new addition to the list of TAG tools. VECAT is a spreadsheet tool for calculating carbon emissions from road traffic on a link-by-link basis. Users enter the flows and link distances (perhaps generated by a traffic model), and the tool calculates the emissions. Handily, the results can be pasted straight into the TAG greenhouse gases workbook.

It’s aimed at addressing the limitations of the two main existing tools used for this purpose, the Emissions Factors Toolkit (EFT) and TUBA. TAG unit A3 section 4.3 has been updated accordingly, and includes a recommendation to use link-based tools such as VECAT and EFT in preference to matrix-based tools such as TUBA.

There’s more background on this in my commentary in Local Transport Today issue 925 (30 October 2025) or online at TransportXtra (£).

Climate change adaptation enters the chat

In recent years, TAG and the parallel transport business case guidance have increased their level of focus on assessing and managing a proposal’s impacts on climate change. But climate adaptation – the process of adjusting to climate change and its effects – has barely featured in appraisal guidance or practice.

DfT has begun to rectify this, with a short addition to The Transport Appraisal Process, their end-to-end guide to the appraisal aspects of taking a scheme from option development through to post-delivery evaluation. The new text recommends proportionately examining how climate change may affect the success of potential options, and considering climate adaptation measures within any intervention. It signposts readers to the more detailed Green Book guidance on accounting for the effects of climate change and other existing guidance.

![Two extracts from ‘The Transport Appraisal process’.

On the left, paragraph 2.4.4. Text is as follows.

2.4.4 It is important that climate change is considered within the appraisal of transport interventions. Climate change refers to long-term shifts in global and regional climate patterns and poses risks to UK transport by damaging infrastructure, disrupting services and compromising safety (for further information see DfT’s Transport hazard summaries2 ). Climate adaptation is the process of adjusting to climate change and its effects. Whilst climate adaptation may not be the primary purpose of an intervention, consideration should be given to climate adaptation measures that can be deployed to improve the reliability and safety of transport interventions, reduce damage costs and ensure long-term savings through avoided losses, and wider social and environmental benefits (for further information see Triple Dividend of Resilience

[Footnote] 2 Transport hazard summaries (2025). Department for Transport, Met Office and Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. Provides information about hazards that can impact UK transport.

On the right, paragraph 2.10.13. Heading is ‘Climate change impacts’. Text is as follows, omitting the footnotes.

2.10.13 Analysts should consider the available evidence to proportionately examine how climate change may affect the success of potential options. This includes exposure to acute climate hazards such as flooding, extreme heat and drought, and chronic climate risks such as sea level rise, gradual temperature change and shifting weather patterns. Where appropriate, Defra’s climate screening questions7 and DfT’s Climate Risk Assessment Guidance can be used. The assessment of potential options should take into account options that are resilient to climate change by exploring possible climate adaptation solutions (examples available in Accounting for the effects of climate change).](https://grahamjames.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/TAP-climate-adaptation-guidance-1024x384.jpg)

This is welcome. Climate adaptation is one of the many aspects of an infrastructure project that are not just technical engineering decisions (or standards to be met unquestioningly) but can affect the project’s value and outcomes – as well as its cost and deliverability. Appraisal and business case teams can add value by making sure these decisions are actively made, well-founded and evidenced.

The new guidance probably won’t change practice on its own. But it’s a marker, and hopefully a first step towards bringing decisions on climate adaptation more into day-to-day scheme development and appraisal practice.

Minor updates, clarifications and corrections

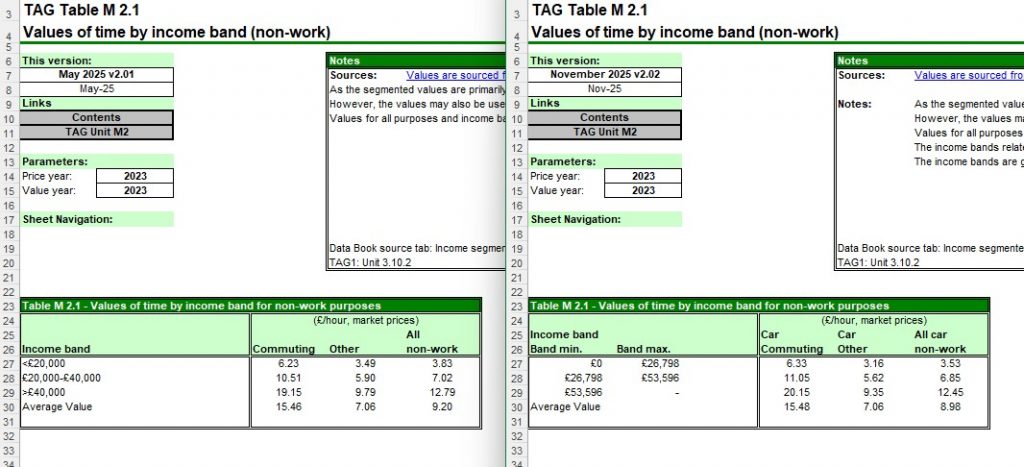

Corrections to values of travel time: One of the most familiar parts of the TAG Databook is the section with values of travel time (VOTs) by journey purpose, mode or distance (tab A1.3.1 onwards). The latest update has a minor technical correction to how the VOTs in A1.3.1 are calculated. But the resulting changes are just a fraction of a percent, so won’t affect anything much.

There are other VOT corrections in one of the databook’s more obscure corners. Lurking at the back, in tabs M2.1 and M2.2, are VOTs split by income band as well as mode and purpose. Their main use-case is in variable demand modelling (VDM) for situations when tolls or charges are a factor. These values have changed more significantly. If this affects you, note that the income bands now change according to the price-year and value-year. The corresponding guidance, in Appendix B2 of TAG unit M2.1, has also been updated to match.

Correction to VDM advice on elasticities in realism-testing: Also for VDM practitioners, the unit M2.1 advice on realism-testing has been corrected to reflect the previous (May 2024) update to the recommended elasticity ranges.

Reflecting the latest PDFH on rail performance impacts: In the rail world, the latest version (6.1) of the Passenger Demand Forecasting Handbook (PDFH) has introduced a new approach to estimating the impact of performance (jargon for delays and cancellations) on demand. This is now reflected in TAG units A5.3 and M4.

Clarification on MECs: Unit A5.4 on Marginal External Costs (MECs) has a minor wording change (in paras 2.7.7 to 2.4.9) clarifying when to use the average impacts across the week and when to use the values split by time of day and region.

Minor correction in unit A2-4: Finally, and not advertised as a forthcoming change, there is a small correction in the text on ramp-up of dynamic agglomeration benefits in Unit A2.4 (para 4.2.2).

And that’s what’s new in TAG for December 2025.

Post updated 3 Jan 2026, with Tag-at-a-Glance now updated and adding the handy graphic.